In this blog post, I will start with discussing the word "quest" and its meaning(s). Two semantic layers will be differentiated and following that, a pragmatic definition will be chosen, which shall capture our usage in the context of games. A collection of associations is gathered then, which shall serve as inspiration for further exploration in future posts.

In the second part, I try to incorporate some quest structures and quest narration into Among Us. But first a small history of the quest as a word.

Where does the term "quest" come from?

The term "quest" is an old one, stemming from medieval English and French (Link). When pondering it, many people probably think of myths, legends and great tales in folklore: The search for the holy grail, for instance, is a famous quest. Heroes go on a (often allegorical or symbolic) quest, which usually has been given to them by someone (or something). The hero is faced with many perils during his journey and is often changed by it. Joseph Campbell describes a pattern in such tales, which he calls the hero's journey. In the way it was described here, the term has been reused in modern literature too: In J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings the protagonists go on a quest to destroy a ring.

As Jeff Howard in his book on quests mentions, many tabletop roleplaying games draw heavily from modern fantasy. Prominent TRPGs like, for instance, Dungeons & Dragons explicitely cite Tolkien's works as inspiration (Link).

Early computer roleplaying and adventure games were in turn much inspired by the fantasy TRPGs and concepts like Campbell's hero's journey. And this is, how the term "quest" most probably found its way into computer games.

As of today, we still find quests mainly in roleplaying computer games with a fictional setting, especially when the setting is in a fantasy-world. Prominent are Bethesda's The Elder Scrolls series, the World of Warcraft universe by Blizzard, the Witcher adaptions done by CD Projekt RED or the Dragon Age games.

But we find quests also in non-medieval fantasy games (sometimes under a different name, such as missions): Mass Effect, Fallout, Cyberpunk 2077, Assassin's Creed, GTA are examples.

What are Quests in Computer Games?

Game Designers have used the quest concept as a means to structure sections of the played game. Here I try a first definition: In games, quests are often a series of events and goals, where subsequent event(s)/goal(s) are only revealed, when previous goal(s) have been reached or some event has happened.

Unless otherwise stated, we will use the term in this sense, from now on. How do quests relate to other game elements? This is a crucial question for understanding quests, quest design and quest-games, but is also a hard one: Games have a lot of quite different elements, of whose relation to each other even current research is not fully decided yet. This topic will appear a lot in this blog and it is hoped that in the end the relations of quests and computer games will have been cleared up to some extend. We shall begin here with a rough outline.

Being a structural component, quests share traits with anything that structures the game in any way in opposition to the player agency - whoever makes a quest has thus the chance, to influence what the player perceives. Quests are often used to tell a somewhat delimited story(-section) which is sometimes placed in a greater narrative. Being a series of events/goals, they are a game part which is meant to motivate players to continue playing. Quests have a beginning and an ending - defined by the first and last event(s)/goal(s). By following the quest's trace, player invest multiple intervals of playtime - a quest thus shows itself too in its timely concretization. Quests usually take place in a game world where player actions are possible - both world and action serve as source for events/goals. At last, there are so called branching quests: In these quests possibly different events/goals are presented depending on (possibly unconscious) choices the player has made.

With that, I will content myself for now. We will now skip to the part, where I discuss my quest design for this week.

Further Reading

Among Us

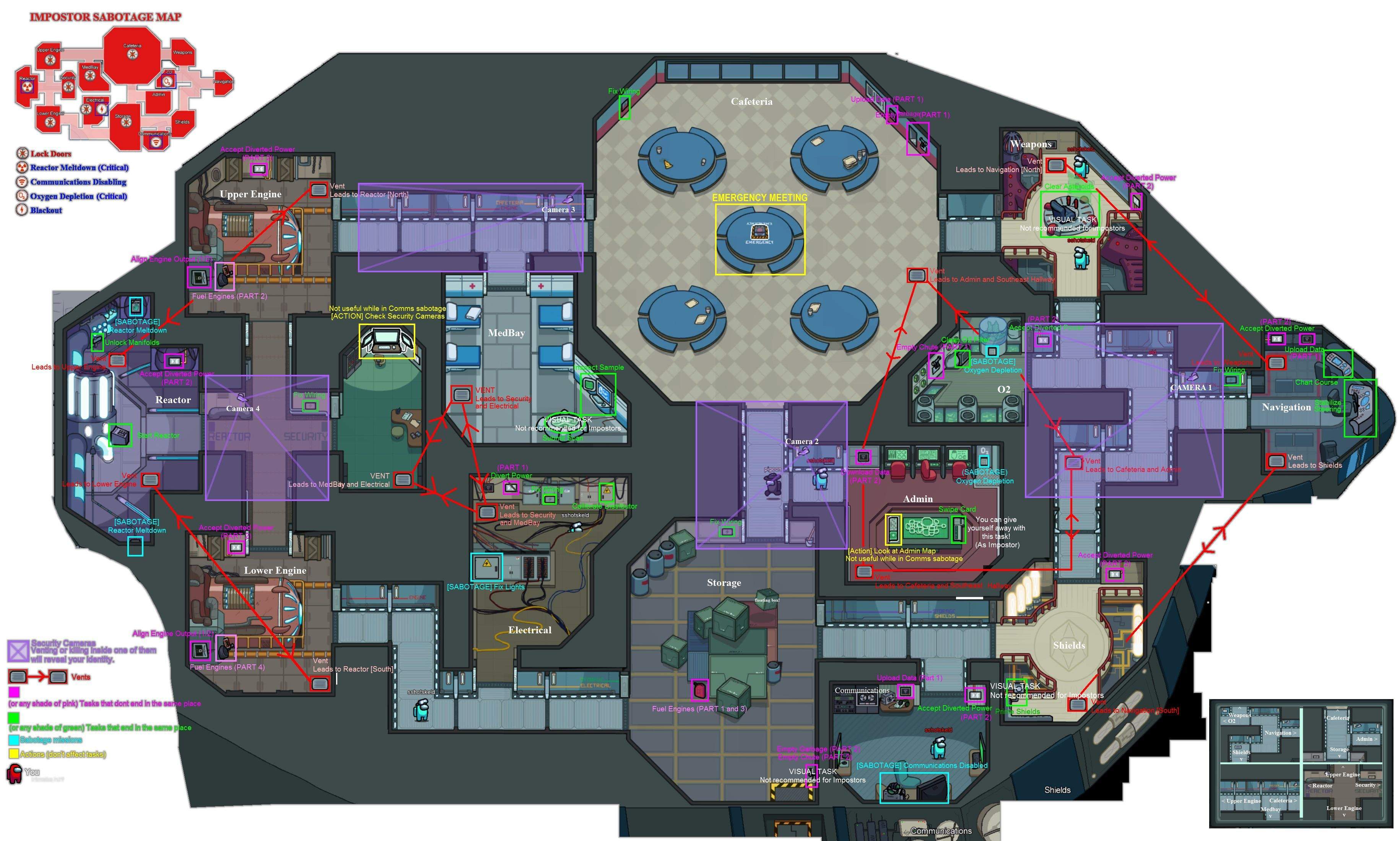

Instead of doing everything from scratch, I began with devising a narrative task-chain for the game Among Us. In this game a group of players is on a space ship, represented by a map (here from a bird's perspective):

At the start the players are divided into two groups: Impostors and Crewmates. The latter have the goal to eliminate all Crewmates (which can be done by various means). Crewmates, on the other hand, have different tasks to do, which, if all completed, will let them win. Crewmates can also win by finding all Impostors. All Crewmate tasks are location-bound: They are only found in specific rooms. Every task consists of a small riddle which is usually quite easy to solve. On the upper left corner of this picture is an example for the task list, that a Crewmate might get:

In its current form, Among Us has a quite simple narrative (which is not necessarily a bad thing). The story is that of a space ship crew, where for unknown reasons it is clear to everyone that there are impostors (alien parasitic shapeshifter) among them. Nonetheless the usual maintaining has to be done, to keep the ship running. In a tense atmosphere step by step Crewmates are murdered such until either they are all killed or until the Impostors' identities were uncovered.

The story is very much present: There are few cues to any past or future things and this is very sensible: After all, the game is in essence about social deduction, tactics and strategies rather than narration or the world. However, the environment and the narrative roles Impostor and Crewmate serve as corner stones and prevent from the game becoming abstract. When adding more narration to the game, one thus has to be careful, to not disturb the "presentness" too much.

The main question for me then was: How could one efficiently change/add missions and their corresponding locations/riddles in such a way, that they tell a little story while the philosophy of the game is preserved?

An "Among Us" Mission: A deadly Journey

First of all I had the idea of giving the players predefined task chains instead of rather random tasks (as it is now). One such predefined task chain ("mission") then provides optional narrative information bits for the interested player. I tried to do selection and order of the information bits in such a way, that it helps constructing a mental model of the narrative. Level design techniques and the task log shall guide the player in the right order through the rooms.

Here are the information bits and how they are integrated into the map:

- An old newspaper article reporting how a crew of astronauts is sent into a far away corner of the galaxy.

The newspaper is seen beside the garbage slot in the cafeteria. - A notice in your portemonnaie reading "He's dead. What now?"

Can be seen while doing the "Swipe Card" task in the admin room. - A coffin with the name "Captain 12" on it.

Stands in the storage room. - Various supplies and scientific devices, some in boxes, whose labelling indicate that they contain further scientific devices.

Stands in the storage room, too. - A newsletter displaying headlines from their home planet.

Placed on a wall in the corridor above the communications room. - A display showing the distance from current position to home planet.

Can be seen when doing the "Chart Course" task. - A writing saying "What is the lesser evil? Who is it?"

On a Post-It next to the "Clean O2 Filter" task. - A whiteboard with a lot of writings on it. Most of them are concerned with long-, mid- and short term plans of the crew. It seems that the scientists plan to build more advanced scientific devices at the "Polus research base" and investigate the so called Dyson Sphere.

The whiteboard stands as interactable object in the corridor between Cafeteria, MedBay and Engine. If interacted with, the writings on the board can be read.

And here follows a possible task chain to this mission (note that some tasks consist of several parts):

- Upload Data 1/2 (Cafeteria)

- Empty Garbage 1/2 (Cafeteria)

- Download Data 2/2 (Admin)

- Swipe Card (Admin)

- Fuel Engine 1/3 (Storage)

- Empty Garbage 2/2 (Storage),

- Chart Course (Navigation)

- Fix Wiring (Navigation)

- Clean O2 Filter (O2)

- Clear Asteroids (Weapons)

- Fuel Engine 2/3 (Upper Engine)

- Fuel Engine 3/3 (Storage),

Below is shown how a possible walk through the above task chain could look like (the numbers reference the information bits). By following the tasks step by step, the narrative informations can thus be discovered.

I devised this based on a sketch where I denoted the three main paths through the map and the two central hubs, the cafeteria and the storage:

- highlighting the tasks in the task log in that order, which is estimated best narrative-wise (but it should always remain possible to do them in random order, this is especially due to exceptional events, in which the intended path would be left anyway)

- add little interactions which are optional and provide narrative context (like the whiteboard I added above): this could be a nice gameplay option too: Crewmates would have to balance doing tasks with exploring narrative context

- it might be interesting to add small triggered events, based on interactions with the environment and through progress in tasks

Ideas for Feedback

- What understanding do you have of quests in games?

- Should the narrative bits of my design maybe be better scattered over several task chains with more non-narrative tasks?

- How else could storytelling be sneaked into a social deduction multiplayer game?